The Lady in the Cellar – Sinclair McKay’s journey into 1870’s London

Sometimes a BookTrail can be all the more interesting as it involves a trues tory, an historical true story and a murder mystery to boot. If the crime is so far in the past that the city and the street where it happened are either unrecognisable or gone altogether it gives the whole story another level of intrigue…

What can you tell us about finding the story and wanting to write about it?

Victorian London seems to exist largely as a realm of the imagination: a fogbound world conjured by Dickens and Conan Doyle. Therefore my curiosity about the reality of life in those streets is all the sharper: from the food and the pubs to the very first underground trains. And I came across this story through reading old newspapers. It immediately gripped not just because of the weirdness of the murder mystery – the discovery of an almost mummified well-dressed lady in the coal cellar of number 4 Euston Square in May 1879 – but also because the lives of those involved were so compelling. Paradoxically, there are some murder stories that you would be fascinated to read even if there was NO murder in them. Here we had a highly respectable Bloomsbury boarding house, owned by a young couple – Severin and Mary Bastendorff – who lived there with their four children. Severin, born a farm boy, now enjoyed the trappings of middle class life: from shooting weekends to fine wines. He and his brothers had emigrated from Luxembourg; in a few short years they had built a very successful furniture business. The tenants in the house tended to be merchants from continental Europe. Here was a home with maids and modern comforts. But this was also a house of secrets. Boarding houses by their nature involved a degree of enforced intimacy; but deep into the nights, there were unfamiliar footsteps creeping up the stairs of number 4 Euston Square…..

How did you research setting? many of the places have now gone.

Certainly the northern half of Euston Square is gone; but there is an abundance of material – written and visual – to be found in brilliant institutions such as the London Metropolitan Archives in Clerkenwell and the Holborn Library on Theobalds Road. Added to this, the wider area of St Pancras and Somers Town and northern Bloomsbury is filled with echoes: from the amazing reclaimed Victorian industrial architecture on the canal to the north of St Pancras, to the grandeur of the surviving houses on Mecklenburgh Square (below) to the still powerfully atmospheric St Pancras Old Church, with its graveyard reconfigured by Thomas Hardy. When pacing London’s back streets, it is never too difficult to summon the past.

Did you visit some of the places/nearby and what did you find out?

I was quite taken aback to discover that the busy Euston Road had an abundance of dairies in the late 19th century. It seemed such an incongruous thing. The milk they sold had either been brought in by train to Paddington and Euston, or indeed was produced by cows kept on the premises, sometimes in basements. Cows in basements in central London! At that time, tram operators were experimenting with having their vehicles drawn by specially imported Spanish mules.

These days, round the back of Kings Cross station, there is a building with a sign proclaiming ‘The German Gymnasium.’ It is a rather smart restaurant – but in 1879, it was in fact a gymnasium for the German community. It also hosted concerts and grand banquets. Speaking of which, I greatly enjoyed following Severin Bastendorff’s footsteps, exploring the history of London’s flourishing German community in the late 19th century. Long before there was a European Union, there was freedom of movement: anyone from the continent could come and live in Britain without any restrictions or indeed any kind of bureaucracy. And at the time of this story, the enthusiasm for all things German extended to art, music, restaurants, books….and pubs in Bloomsbury started stocking German lagers!

What would be Euston Square today:

Any stories you can tell us about the writing of this book?

One of the key figures in the story eventually suffered terrible mental health problems and was finally removed to an asylum north of London called Colney Hatch. I had always associated Victorian asylums with a very particular kind of horror: imagined them to be terrifying institutions filled with unthinking cruelties. Yet as I read deeper, a wholly different story emerged; one that I found very moving. Certainly Colney Hatch was a deeply forbidding prospect; but the lives of those within – patients and doctors – were touched with warmth and many instances of understanding and kindness. At least, that is, in the mid to late 19th century, the time of this story. So many conditions, such as paranoid schizophrenia, were not understood; but doctors sought to bring their patients a sense of safety and security. From walks in the country to Turkish baths, there were efforts of all sorts to alleviate suffering. Now: the institution certainly went through ups and downs in later years, and the idea of being committed there was widely regarded with fear. But writing this book gave me a glimpse I never thought I would get of wholly unexpected compassion.

St Pancras Old Church today

Why did this crime in particular fascinate you?

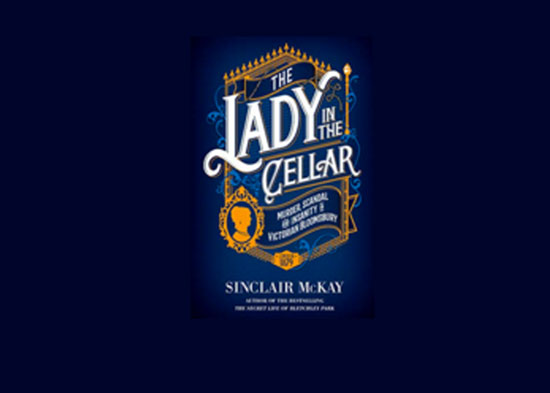

Partly because I was so intrigued by the tragic victim: a pleasingly eccentric, (broadly) blameless and wealthy old lady called Matilda Hacker, who dressed in the style of a teenage girl, with auburn ringlets and hooped skirts showing off her ankles. She was skittish and unpredictable and exasperating – particularly for those like local authorities who were owed money by her. She moved from boarding house to boarding house, apparently to escape creditors whom she could actually very well afford to pay! But she also charmed those who met her. Matilda Hacker was obsessed with tarot cards and what she called ‘the Book of Dreams’, a volume of celestial prognostications. At any boarding house she stayed in, she would give readings from The Book of Dreams, with every appearance of taking it perfectly seriously. And when she went to live at 4 Euston Square, she captivated the Bastendorffs’ young children. Matilda Hacker was psychologically complex but also appealing. How then could she have ended up dead in a cellar with a clothes line wrapped tightly around her throat?

It’s a bit Dr Crippen/10 Rillington Place isn’t it?

I would say that it is more layered than either of the above: more shade, more light as well as dark. This isn’t just a story about murder: it’s about the extraordinary repercussions and the revelation of secret passions that follow the discovery of the body. This is the life of a house, and a family, being ripped apart by the new medium of the mass popular press. It’s also a story of a young maid who moved from rural Devon to London fighting for her survival in the Old Bailey – and her terrible subsequent revenge against the man she considered to have wronged her. In other words, the murder itself enables us to explore in detail the underside of Victorian domestic life that we rarely see: a world of conflict between servants and masters, and a realm of seedy and furtive sexual relationships. Unlike 10 Rillington Place, which is a story of utter depravity and evil, this is a mystery so baffling that at one point, the coroner could not even say with complete certainty if it was murder. The fascination lies in the way that the discovery of the corpse violently changed the course of so many lives, innocent and not so innocent.

Are you sad it was never really revealed who the killer was?

No. The story is as mysterious now as it was to Victorian newspaper readers. I have a theory, which I elucidate in the final chapters. But it can only ever be that. The fact that the case was never solved gave an edge of poignancy to the horror. It also meant that for many decades afterwards, Euston Square was associated with the macabre crime. Much to the chagrin of the posh residents! Indeed, even as early as 1880, they were pushing for the name of the square to be changed. Eventually they prevailed. Now, to the south of the Euston Road is the surviving terrace of the square, renamed Endsleigh Gardens. (above)

Do you like giving people from the past a voice?

It is not so much giving people a voice; but more about listening to and hearing those voices as they were. In this case, there were copious police notes, court transcripts, letters and personal accounts: so the voices of key figures such as the maid Hannah Dobbs, the landlord Severin Bastendorff, his brother Peter and others came through with terrific clarity. Style of speech is always fascinating: as indeed are antique colloquialisms. But the Victorians could also be very direct: some of the language used in the court cases concerning sexual relations is startlingly frank!

Thank you Sinclair for a fascinating insight into the story!