#Authorsonlocation – 1600s Amsterdam, Descartes and more

The Words in My Hand is a stunning book on so many levels. It sings from the page with its lyrical writing but the story behind it is based on true fact – the story of a maid working in 17th Century Amsterdam. It’s the story of a maid, Helena Jans whose path in life crosses with that of a enigmatic Frenchman – Rene Descartes.

If you need a novel which immerses you in the time and place – where men wear ribbons on their shoes, where the sailors shouts colour the sky by the harbour, where people collect quills in jars, and where the imposing homes on the Herengracht reflect the sunshine from their windows, this is the novel for you….

Author Guinevere Glasfurd dons her best bonnet, picks up a a quill and ponders the meaning behind choosing Amsterdam and the Dutch Republic as a location…

BOOKTRAIL THE WORDS IN MY HAND

The Words in my Hand

On choosing the location….

Funnily enough, I did not set out to write a book about the Dutch Republic. I knew I wanted to write about Descartes, but it came as a complete surprise to me when I learned that he lived most of his adult life in the Dutch Republic, not France. In fact, Descartes seemed eager to be as far away from his homeland as possible and returned infrequently.

The Dutch Republic in the seventeenth century was a comparatively tolerant country and largely free of the wars that ravaged other parts of Europe. It was the time of the Inquisition, when women were burned as witches and heretics put to death. Descartes was not a refugee, but the country provided a refuge of sorts, as well as a degree of intellectual freedom and space to work relatively unhindered.

Rene Descartes

Descartes’ Correspondence makes it clear why he chose to settle there. Writing about Amsterdam in 1631 he noted,

‘…I could live here all my life without ever being noticed by a soul. I take a walk each day amid the bustle of the crowd with as much freedom and repose as you obtain in your leafy groves, and I pay no more attention to the people I meet than I would to the trees in your woods or the animals that browse there. The bustle of the city no more disturbs my daydreams than would the rippling of a stream…Whenever you have the pleasure of seeing the fruit growing in your orchards and of feasting your eyes on its abundance, bear in mind that it gives me just as much pleasure to watch the ships arriving, laden with all the produce of the Indies and all the rarities of Europe. Where else on earth could you find, as easily as you do here, all the conveniences of life and all the curiosities you could hope to see? In what other country could find such complete freedom, or sleep with less anxiety, or find armies at the ready to protect you, or find fewer poisonings, or acts of treason or slander?’

Descartes, letter to Balzac, 5th May 1631.

The importance of location

It structures the novel; each section begins somewhere new.

The novel follows Helena’s journey across the Dutch Republic in the 1630s. The story begins in Amsterdam, when Helena meets Descartes at Mr Sergeant’s house, where she worked as a maid. It then moves to Deventer, Leiden, Santpoort, Amersfoort and Egmond aan den Hoef on the north sea coast.

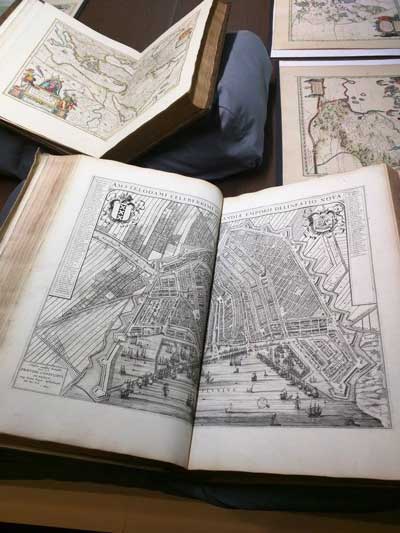

Blaue map of Amsterdam (c) Guinevere Glasfurd

When I visited Egmond aan den Hoef, which is nestled in the lee of some spectacular sand dunes, I had a very clear sense of Descartes and Helena in the landscape; of them being together and trying to remain hidden. Think of how flat the Netherlands are, how open and exposed it all is. The dunes provide a fascinating contrast.

Sand dunes at Egmond aan den Hoef. (c) Guinevere Glasfurd

Descartes wrote, ‘In order to live well you must live unseen.’ In large part, this is a reference to himself, to his work, to keeping out of trouble. But it also hints at Descartes’ affair with Helena. They were not social equals. She was a Calvinist, he a Catholic; marriage would have been out of the question. If news of their affair had become public, it would have ruined them both. There were powerful clerics in Utrecht who would have taken great pleasure in Descartes’ demise.

On research

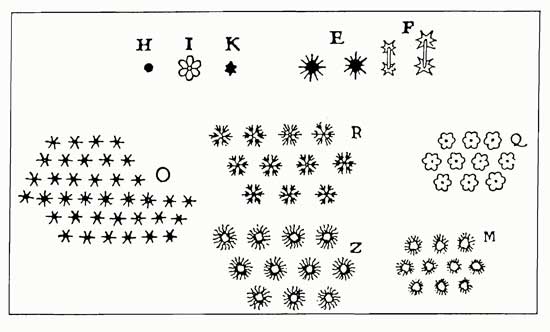

A grant from Arts Council England paid for two research trips to the Netherlands. I read widely: histories and biographies of Descartes, and also his own work. His Correspondence was key. It not only helped me to find Descartes’ voice, but was a way to map across what was happening in his life on to the timeline of my novel. Descartes was one of the first to describe the structure of snowflakes and was working on this when he was in Amsterdam. This became a scene in the novel when Descartes and Helena go out in the snow and catch snowflakes.

Descartes snowflakes (c) Guinevere Glasfurd

The snow fell more heavily, clumping in large soft, flakes.

‘Keep your hand there,’ he said. ‘That’s better. Four, five, six. Six radii. Perfect hexagonal structures.’

Hexagonal – what a word. If it had a taste, it would taste of cherry.

Researching Helena was much more difficult. We don’t know when she was born, or what she looked like. Only three documents exist in the archive that mention her. In a way, this set me free to imagine who she might have been. It is known that she and Descartes corresponded but that these letters have been lost. Answering the question how she might have learned to write became central to the novel and to revealing her backstory and character.

Descartes’ and Helena Jans’ Amsterdam – Booktrail it here: The Words in My Hand

If you’ve ever visited the Anne Frank house, then you have perhaps unwittingly walked past the house where Helena worked and Descartes lodged, which is nearby, and where their affair is thought to have begun….

6 Westermarkt, Amsterdam. The house where Descartes lodged in 1634 (c) Guinevere Glasfurd

My book is sometimes compared to Tracy Chevalier’s Girl With a Pearl Earring. Although both novels tell the story of a maid and a ‘great man’, Chevalier’s protagonist is fictional. Helena, on the other hand, lived. She had an affair with Descartes and likely knew him for a decade or more at a pivotal time in his life. It struck me that few historians had shown any real curiosity towards her; her significance, passed over, or dismissed. Yes, I wanted to tell (to recover) her story, but in doing so, I wanted to show how she might have mattered to Descartes and how she might have influenced him. I began to see that fiction could be a way to interrogate the past, to challenge how history is written. I had not realised that at the beginning, but it became central to my novel in the end.

Seventeenth century maps were very useful indeed and many are available online as high-resolution images. I spent hours studying them, thinking about where Helena’s work as a maid might have taken her and imagining her journey on foot.

Dutch genre paintings of the time were also an important source. Women become visible in these paintings in a way they hadn’t been before. We see domestic interiors; maids at work; wealthy women reading and writing letters. The paintings are often highly moralistic, but provide a wealth of detail. The Rijks Museum in Amsterdam has a fabulous collection and is well worth a visit.

On recreating the atmosphere..

The novel is told in the first person from Helena’s point of view. I want the reader to feel as if they are stepping into the story, right by Helena’s side.

It was interesting to reimagine Descartes as a younger man; to strip away the ‘great man of history’ narrative that surrounds him. He still hadn’t published when he met Helena, and comes close to destroying work he’d been writing for several years. But something changes him, and the years he knows Helena are some of his most productive.

Guinevere Glasfurd

On Helena Jans…

Helena was a woman of her time. I did not want to create a faux feminist protagonist. This would not only have been ahistorical but not true to who I think she was. It mattered to show the constraints of the time and to be true to the historical context. It was absolutely, without question, a man’s world, and man was made in the imagine of God. This did not mean that Helena did not have agency. She did. But she was vulnerable. She was vulnerable to the whims of men, to their power, their ignorance, their prejudice. In the novel, I place her struggle for learning on a level with Descartes’ quest for reason. In telling the story from her point of view and not Descartes’, I hope I have helped to rebalance history a little and thrown some light on her possible historical significance.

With a million thank yous to Guinevere for such an interesting and insightful tour of Descartes’ and Helena Jans’s Amsterdam and more

BOOKTRAIL BOARDING PASS – The Words in My Hand

Twitter: @guingb Facebook: /GuinevereGlasfurdBooks Web: guinevereglasfurd.com/