Elizabeth Brundage – All Things Cease to Disappear

Elizabeth Brundage is sitting opposite me at this very moment. Booktrail her novel here – we’re off to Uppstate New York

We’re in a very smart and upmarket cafe and we’ve chosen a selection of posh cakes, strawberries and champagne! I know! This cuppa and a cake has gone up a notch!! This is a very nice establishment so I’m honoured Elizabeth has picked it. I start to flick through the hardback of the novel on the table and the ghostly design .But we’re getting a bit hungry and fifteen minutes later the waitress comes over to put the cutlery on the table – I’m about to ask about our order when I move the book to let her lay the table – and she spots the title of the novel. OOh I am sorry she says and hurries off. I’d said nothing but this book I tell Elizabeth is going to be very useful as well as enjoyable in the future!

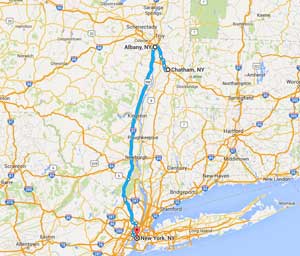

You set your novel in Chosen, NY. Is this based on anywhere in particular?

The town in the novel is loosely based on a small town in upstate New York called Chatham – although it could be any one of several upstate towns. The fictional town of Chosen is situated in the beautiful Hudson River Valley, where many of the early landscape painters like Inness worked. For those of us who live up here, the river is an essential artery to the heart and soul of the region. The area, originally established by the Dutch in the seventeenth century, is lush and green and very beautiful, and many of the original homes and barns remain. I love old houses and have lived in them most of my life and I like to write about people who live in rural places who inhabit homes that were built to sustain the centuries.

You mention the inspiration you got from the painter George Inness who was renowned for painting landscapes of Upstate New York. What fascinates you about him and how did this influence your work?

Ever since I was a little girl growing up in New Jersey, not far from where George Inness once lived in Montclair, I have loved his work. I think I always saw a certain mystery in his paintings, a peaceful ambiguity. The paintings were never about rendering a subject. Instead, Inness opens a spiritual window, inviting the viewer to engage in the experience of nature, the beauty of solitude, rather than to simply admire it.

Which of his paintings would you recommend we see – are any of them of ‘Chosen’?

There were several Inness paintings that helped me to visualize the rural town of Chosen. One that particularly inspired me was Home in Montclair, which Inness painted in 1892. The painting so brilliantly conveys the melancholy and isolation of rural life and the sense one might feel of being a very small part of the vast landscape – both at one with nature and at its mercy. If you look at Inness’s Sunrise in the Woods, 1887, you see this beautiful yellow glow that suggests the warmth of the sunrise and also the sense that we are never alone and that immersion in nature is a spiritual act. This element, as well as Inness’s Swedenborgianism, served the novel well and enabled me to consider some of the larger important questions many of us share about life and death and faith and the possibility of an afterlife.

You open your novel with a very brutal scene and then take the reader back to the start as it were. Did you write this scene first or how did you plan the novel?

The initial inspiration for the book began with an actual unsolved murder that occurred in the eighties and remains an open case. I had heard about the story in the 90s but didn’t begin writing about it for another ten or so years. There are many reasons for this. First, I don’t consider myself a crime novelist and I’m much less interested in solving crimes than I am in exploring why they happen in the first place. I was much more interested in the characters who had some connection to the murder rather than in the particulars of its investigation. In terms of structuring this book, I took a more meandering approach, as if I were exploring this town and countryside on foot rather than by car, if that makes sense. I like to say that writing a novel – at least in the very early stages of the process – is something like having a bad case of amnesia. You have a vague sense of clarity. You know your story is somewhere in your brain, you just have to remember it. As time goes on, the colors of the world you’re creating become more vivid – the people step into the light. It’s your characters that lead you through – they know exactly where they’re going. As their interpreter you have to trust them, you sort of have no choice.

Why do you choose not to use speech marks?

My hope was to achieve absolute clarity on the page without the ornamental direction of the marks. To some degree we have become complacent readers, consumers of entertainment. If at first the lack of these marks disarms the reader that was okay with me. I’m asking the reader to be patient, to read carefully, to trust me. To simply absorb the words as they come. I wanted no barriers between the reader and the text and for all parts – dialogue – description – to share equal importance. I also think there’s a kind of poetic purity to the words as they run down the page and the dialogue reads almost like a blank verse poem.

You’ve worked in both films and now fiction. How did the earlier screen writing experience infiltrate your work?

I learned to tell a story in film school, and that has proved invaluable to my work as a novelist. Screenwriting depends on a progression of events that lead to some meaningful outcome. I think this is a very good structural tool in writing novels. Also, I do believe it’s important to always keep your audience in mind – who that audience is and why you’re asking them to read your work.

Can you tell us something about Albany that most of us Europeans might not know?

I like to call the city of Albany Kafkaesque. It’s the state capital, which means there are a lot of state workers around and nondescript buildings full of strange and essential departments where these people go to work. The history of this city is fairly evident, with many old buildings interspersed among the new. There’s no pretense here. The people are real, hard-working, Visually, there’s a grittiness to central Albany that suits me, and within a few miles you can find yourself in the most glorious rural countryside, with the Adirondacks, Catskills and Taconic mountain ranges, and of course the iconic wilderness of the Hudson River Valley.

Have you ever been in a real haunted house yourself?

When my daughters were small – before our son was born – we rented this charming cape in an historic hamlet that turned out to be haunted. My daughters, who were 3 and 6 at the time, told me stories about three little girls who had died in a fire. All sorts of unusual things began to happen that convinced me there was some truth to it. For example, we’d get into bed and night and feel the mattress begin to shake as if someone – a child – were jumping on the bed – there’s more about this on my website (www.elizabethbrundage.com). Unlike the usual stuff of horror movies, the experience sort of opened me up to the possibilities of ghosts as haunted souls rather than monstrous forces of evil. It inspired me to create the character of Ella in the novel.

George is a very unique and unsettling character. How did you create him?

There are many things that go into creating a character – and there’s a bit of magic involved. A writer’s greatest tool is her instinct. I knew I wanted to write about an individual who gets away with murder and I tried to consider all of the possible elements of that sort of personality. Then George showed up on the page one day and he took it from there. As it turned out, he was a fascinating, highly charismatic guy. In the novel, he uses his intelligence and charisma to attract people and make good use of them. There’s a reason that the word logic is in pathological – and the more I got to know George Clare, the more I understood that he’d developed a strategy for maintaining his connection to the world, one that, while entirely aberrant to us, made perfect sense to him.

With many thanks to Elizabeth today. We’ll leave you now as the second round of strawberries have arrived. Be sure to head over to elizabethbrundage but we can’t promise champagne or strawberries mind!