Meet the Translator – Quentin Bates

On Iceland’s National Day what better way to celebrate than with a man who knows the country, the landscape and the literature like the back of his hand. Quentin Bates, an author in his own right, is sitting waiting in a log cabin, warming the kettle on the stove for our visit. It’s chilly but he’s told us he provides blankets and cake so we’re good. If we ever get there through this snow that is.

On Iceland’s National Day what better way to celebrate than with a man who knows the country, the landscape and the literature like the back of his hand. Quentin Bates, an author in his own right, is sitting waiting in a log cabin, warming the kettle on the stove for our visit. It’s chilly but he’s told us he provides blankets and cake so we’re good. If we ever get there through this snow that is.

Well here we are – somewhere in Iceland – there’s lots of snow around that’s for sure. And flags and parties as people celebrate national day! So Quentin…..

You’re a writer and translator and have just finished working on the Ragnar Jónasson’s “Snowblind’. How did you find that and how different were the experiences?

It was a remarkably rewarding experience. I had done a lot of translation before, but mostly very dry news or technical stuff that absolutely doesn’t need any kind of interpretation. So getting to grips with Snowblind was quite a challenge. I wasn’t sure to start with if I could pull it off, and I think it’s safe to admit that now. But it worked out very well. Ragnar writes a very clear, almost an old-fashioned, Icelandic that’s a pleasure to read.

There’s inevitably some interpretation that has to be done and two translators given the same piece of text could come up with wildly differing versions. That’s the hard part, and it’s also the fun part that keeps the grey cells buzzing – working out what the author meant rather than what the author actually wrote, and trying not so much to keep the nuances and subtleties of meaning but to transpose them into English. The real challenge is with idioms and jokes, especially if there’s a play on words, as they the translator has to find something suitable that is faithful to the feel of the original when a direct translation would be more precise but could completely lose that feel.

You have deep links to Iceland. Can you tell us more about these?

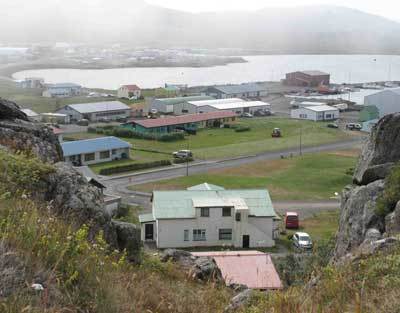

I went to live in Iceland and stayed there for ten years. For some of that time I went native, if that’s still an acceptable phrase, frequently not speaking English for weeks at a time. Since returning to England I’ve remained immersed in Iceland, as my wife and I have always spoken Icelandic together. The internet helps as it means I can read the papers every day and have Icelandic radio on in the background while I’m working. I try and get there a couple of times a year, at least, and would spend more time there if I could.

What do you love most about Iceland and what still surprises you?

It’s probably the tranquillity – although that’s not something you get a lot of in Reykjavík. Where I normally go in the north is very quiet. In fact it can be too quiet and after a while I need to get back to the rumble of traffic.

The climate still takes me by surprise, the sheer rawness of the wind and rain when it’s really howling, as well as the distances once you get beyond Reykjavík. Sometimes you don’t dare pass a petrol station without filling up, especially when you know the next one is 200 kilometres away.

How different is Icelandic Noir to Scandinavian Noir?

How different is Icelandic Noir to Scandinavian Noir?

Not an easy question… there’s so much variety in Icelandic crime fiction, just as there is across the whole sweep of Nordic Noir (if Noir is the right expression). To be blunt, we all owe a huge debt to Sjöwall & Wahlöö, and to a lesser extent to Henning Mankell. But Sjöwall & Wahlöö were the forerunners and I’d go so far as to say their books are as fresh and sharp as anything Nordic since.

If there are difference between Icelandic and Scandinavian crime fiction, it’s maybe more in the look and feel of the location itself, and in the social nuances. Iceland is politically very different to Norway, Sweden and Denmark, although maybe closest to Norway in many ways. Iceland leans more to the US culturally than the other Nordic nations, partly a legacy of the long US military presence that also brought rock n’ roll and gas guzzling cars to Iceland. All this filters through into the country’s fiction, not in an overt way, but subtly.

There are only a few Icelandic crime writers available in English translation – Ragnar is number five. There are plenty who deserve to be translated and may yet make the jump. There’s plenty of variety there, some of it pretty hard-boiled, some relatively cosy, some extremely bleak, just as there are huge differences between the work of Swedish or Norwegian crime writers

Tell us something bizarre about Iceland and its language

Icelandic is the Nordic language that has changed least since the Saga Age. For more than a thousand years Iceland was very isolated and the language changed very gradually. But with the advent of cable TV and the internet it has changed probably more in the last twenty years than in the preceding two hundred as a huge amount of English slang and loan words have sneaked in.

It’s pretty impenetrable for an outsider and it’s not easy to learn. Icelandic has a logical grammatical structure and a vocabulary that’s closely related to other Nordic languages, although there are plenty of words that are uniquely Icelandic.

So it’s certainly not impossible. The real problem is that everyone speaks English and if you make a mistake, people will instinctively switch to English, which can make it difficult to make a start practising spoken Icelandic.

My favourite word in Icelandic is mjólkurbrúsupallabrennuvargur – a vandal who sets fire to milk churn shelters.

Well rest assured, Quentin tells us that he is no mjólkurbrúsupallabrennuvargur himself and so we can safely have another cup of tea safe in the knowledge that the milk churn outside is in one piece.

Thanks Quentin for a great chat and we’ll be back to visit very soon to talk about your own books set in Iceland!