#Authorsonlocation – TIMBUKTU – Nick Jubber

Timbuktu – the name conjures up a wave of wonder and intrigue so do you know anyone that’s actually been? Today, Nick Jubber talks about his trails there:

Timbuktu as the mythical city

Booktrail Nick’s book The Timbuktu School for Nomads

Djenne-mosque (C) Nick Jubber

I was fascinated by Leo Africanus, because of the scale of his journeys (he roamed over more of Africa than any traveller up to that time) but also because of his intriguingly ambiguous identity. He was a Muslim, descended from Andalusian refugees who fled the fall of Granada in 1492, who was kidnapped by pirates and fetched up in Italy, where he was christened by the Pope. At the end of his life he returned, apparently, to North Africa, and recovered his original faith. It’s a roller-coaster of a life – so no wonder he’s been cited as an inspiration for Shakespeare’s Othello, and that WB Yeats used to ‘communicate’ with him through 1920s séances! He’s one of those restless figures who leap off the page, gossiping about sexual pecadilloes, musing about trade, boasting about his poetry recitals, carrying the reader back into his time and bringing it to life.

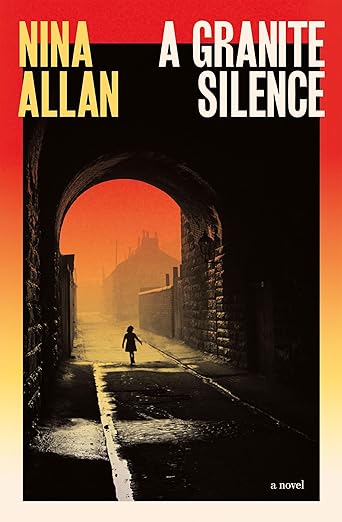

Timbuktu has a strange position in Western consciousness. It’s one of the most famous place-names out there, a by-word for ‘the back of beyond’, yet very little is known about the place itself. I’m fascinated by much-mythologised places, because there’s often such a contrast between the long-term P.R. and the reality of walking about in them. Timbuktu was much richer, culturally, than I’d imagined, with its shrines and manuscript collections and fascinating oral culture, but in many other ways it was poorer, and more troubled.

Timbuktu

Welcome to the middle of nowhere

The greeting, ‘Welcome to the Middle of Nowhere’, is an ironic joke for locals, who know it’s no such thing – after all, they live there. For travellers approaching from the north, Timbuktu was the end of the desert, the last place they knew about; everywhere beyond was ‘terra incognita’, the unknown sub-Sahara. But it’s Timbuktu’s position – at the juncture of the desert and the Niger river – that made it a place of great wealth and influence in medieval times, a centre of Islamic learning, and a cultural beacon for centuries.

In the Sahara

One of my favourite moments was leaving a camp in the Sahara, a few miles north of Timbuktu. The tent belonged to a very chatty well-keeper called Ismail, who sang a song of blessing as we left. It was really soul-stirring, hearing the song as we rode across the valley, while we bobbed along on our camels, and I still get a tingle when I remember it. He was a wonderful host!

Pinasse-on-Niger-to-Timbuktu (c) Nick Jubber

Booktrail Nick’s book The Timbuktu School for Nomads

Worrying times..

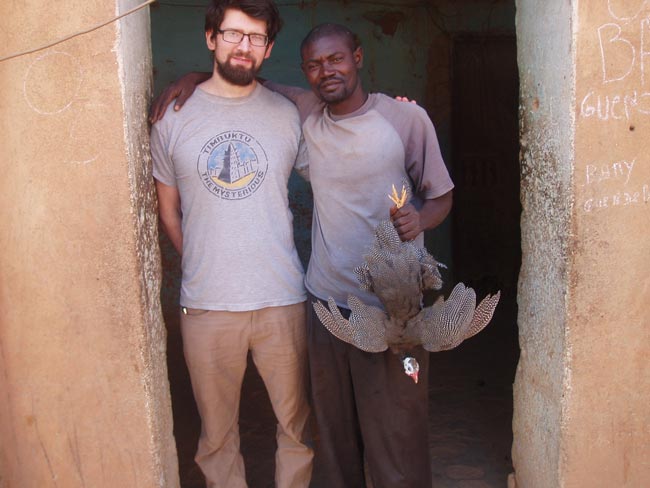

There were a lot of worrying moments, because my journeys coincided with a rapid increase in jihadist activity, so I was reliant on local advice and making friends with people I could trust. I remember explaining to a Malian friend that I needed to get back to Timbuktu (he lived in a nearby town called Goundam), and he advised me against it. But I was keen to return, to see the nomads who I’d planned to travel with, and once he saw I was determined, he did everything possible to make sure I’d be safe. I felt very guilty, and very grateful, for his kindness.

The hardest thing is trust. Working out who you can go along with, who to be wary of. Sometimes it means pushing people away, or being cagey in certain situations. After a group of tourists was kidnapped in Timbuktu, I tried not to reveal my itinerary to anybody unless absolutely necessary, and this often entailed being less open or friendly than I would have liked.

Delievering Guinea Fowl (C) Nick Jubber

How to survive in the desert

here were so many, mostly very specific to life in the desert, but some that have come in handy elsewhere. For example, building fires – my cub-scout memories were a bit rusty, so I learned a few techniques about how to layer the fuel, and also how to light a fire if there isn’t any fuel. There were other, broader lessons – about companionship around a fire, for example, and the art of communicating with people when you only have a few words of their language. One of the useful things about being in the desert was you could often draw pictures in the sand to illustrate what you were trying to say!

As for food – Because of the lack of resources (especially fruit and veg), food wasn’t always my favourite aspect of life in the desert. It was often the methods of preparation that interested me more than the food itself – such as ‘sand bread’, which is cooked in a pit dug into the sand, using the embers from the patch where you brewed your tea, turned around after half an hour. It has quite a chewy, crisp taste.

Speaking their language

There are so many different languages spoken amongst African nomads, and I’m not clever enough to learn all of them (hence the sand pictures!) However, I was keen to communicate with people as directly as possible, so I brushed up my French and studied Arabic for several months before my journey, doing a couple of courses in Jerusalem and Fez. Several of the nomadic communities I travelled amongst were Arabic-speaking (the Berabiche, Saharawis and Beidane), and because of its theological role, I often met people who spoke Arabic amongst the non-Arabic-speaking tribes, so that grounding proved invaluable.

Thanks Nick – that’s quite an account of one amazing journey!

Booktrail Boarding Pass: The Timbuktu School for Nomads

Twitter: @jubberstravels